BASIC GRAMMAR

Basic grammar and Spatial grammar work hand in hand.

All languages have grammar, but Tapissary has two layers of it: the basic shown on this page, and Spatial grammar which is built upon the humble structure of basic grammar. So the basic grammar is a central element of the language. While basic grammar is used about 75% of the time, the other 25% is put to good use; Spatial grammar allows the user to express the degree between the actual and the imagined which has become the lifeblood of Tapissary. There will be a separate page devoted to Spatial grammar. (Historic note: Cyclic grammar which has been a part of the language since 1987 was greatly simplified and renamed Spatial grammar in August 2022. Traditional cycles still exist in the literary scope and very formal speech). So before heading over to check out the more advanced facets of Tapissary grammar, this basics page is a good place to start.

The basic grammar is greatly influenced by English (though as you will see later, this is not true of the Spatial system).

DICTIONARY

As of the very beginning of September 2022, I'm beginning to copy pretty much the entire Tapissary dictionary, which also includes both the glyph and spoken vocabularies. It will take approximately a year to complete, as I must write each glyph with the computer mouse. The second edition of the dictionary was written in 1999 with some 8,000 glyphs, but since Tapissary was originally a written language only without voice, not for another decade did spoken words start appearing. Perhaps only about one thousand glyphs currently have a spoken equivalent, so as I compose this third edition of the dictionary, I need to complete the work in all the aspects.

If you follow the dictionary tab, you’ll see that the vocabulary is written in symbols. There is also a tab on the vocabulary history for those interested in the creation of these symbols. Each symbol, which is called a çelloglyph, also has a pronunciation.

TAPISSARY CAN ALSO BE WRITTEN WITH THE LATIN ALPHABET

I will be transcribing the pronunciation of sentences into the Romanized version of Tapissary along with the çelloglyphs. Please note that the Romanized version is easy enough to read, but not meant to be a strict phonetic alphabet. It has its own spelling personality much as, for instance, French, Spanish, and German do. Please head over to the SPEECH tab for reference on pronunciation and spelling.

LET’S BEGIN…

Here are some phrases. You will notice that verbs do not take conjugation. For example, you say: I like, you like, he like, she like, etc. In the same way, I am, you are, it is, become simplified to; I be, you be, it be.

There is also no change in the direct or indirect pronouns as we have in English. I and me are both simply I. She and her are both she. We and us are both we.

The article “THE”

Now we come to one of the most frequently used words in the language: ‘the’. We have six choices here. One of the roles of this article is to define the physical attributes of the word it describes. In other words, the article ‘the’ is determined by the physical nature of the word it precedes. For instance, when you say, ‘the water’, you use the liquid form of ‘the’. If you say, ‘the wooden board’, you use the hard solids form of ‘the’. If you say, ‘the rock’, you still use the hard solids form of ‘the’. But these forms of ‘the’ are flexible. You are free to exchange them when it’s appropriate. For example, if you say, ‘the rock’, but use the liquid form of ‘the’, this will indicate a flowing form of rock, which will be understood as lava. Likewise, an alternative way to say ice is to use the hard solids form of ‘the’ with the word water, because solid water is ice. Be practical, be playful.

Which form to choose?

I use the soft solids to define animals because we have elastic skin. How about rooms and buildings? Their walls are hard solids, but if you say you are going to the grocery store, are the walls the purpose of your visit? In general, I refer to interiors as air space (gasses) because it is through space that you walk around the grocery store. But you can alternatively use the soft solids form which indicates the foods you are shopping for. Generalization is the key. Certainly, some items you shop for there will be hard solids, but what is the overall picture? You can always use the compound form because it describes a mix. I try to use the compound only when necessary because the other forms are more descriptive. Where do you suppose someone is going when they say they are off to the (liquids) store? If it’s raining, you can say, the (liquid) traffic was heavy.

The choice is always yours and individual, however some degree of practicality helps ease in communication. Wild application of the article will be more effective if it’s used only on occasion to surprise the listener.

NOTE: ‘The’ is the only article that internally undergoes these changes. Only when you want to apply any of the six qualities onto the other articles, place ‘the’ before other articles to give them the same flexibility. Examples: A drink > The (liquid) a drink. We have seven dogs > We have the (soft solids) seven dogs. I know that woman > I know the (soft solids) that woman. Do you understand the my examples above? Placing the six forms onto any other article is not required, but the article ‘the’ of course has no option but to use them.

EXERCIZE

If you want to try this out, I have a few phrases below that use the vocabulary you’ve already seen above.

1. You are the driver? *

2. I remember the shop.

3. She knows the clerk.

4. The bird likes her.

5. The shop clerk likes the bird?

6. You like the bus.

* NOTE: In Tapissary, questions simply have a question mark after them. You do not reverse the subject and verb for a question the way we do in English. “Are you ready?” is stated: “You are ready?”

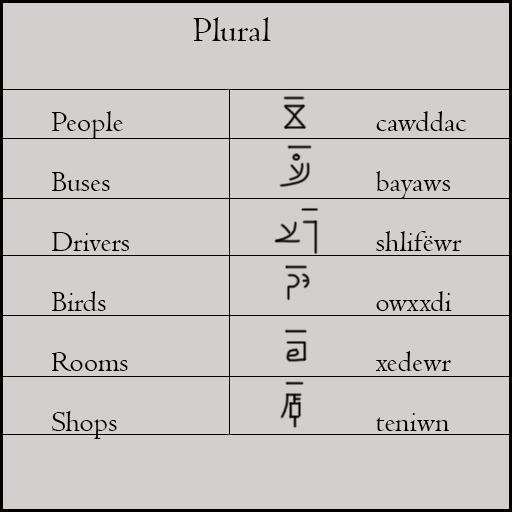

THE PLURAL

GLYPHS

In glyphs, it is shown as a horizontal bar floating above the word. It’s as easy as that, there are no variations.

SPOKEN LANGUAGE

In the spoken language, the plural always falls at the end of the accented vowel of the word. This is easy to tell in the Romanized version. As in French, in Tapissary the tonic accent comes at the end of the word. There is one exception: the vowel preceding a doubled consonant is accented. I’ll write some examples, and capitalizing the vowels that receive the tonic accent:

Remember tonamOs

Bus bayAs

Like amrAz

Rain ëshA

Driver shlifËr

The above examples are typical of the tonic accent coming at the end of the word. But in the case of doubled consonants, let’s see how the pronunciation changes:

Bird Oxxdi

Person cAddac

No clerk tEnni *

Rule: follow the tonic accented vowel with the letter W, which always has the value of a full W, as in the word ‘west’.

Buses bayaws

Rains ëshaw

Birds owxxdi

People cawddac

Remembrances tonamows

Likes amrawz

Clerks teniwn

No clerks tewnni

Drivers shlifëwr

* Don’t worry about the negative yet. We’ll see those formations further down.

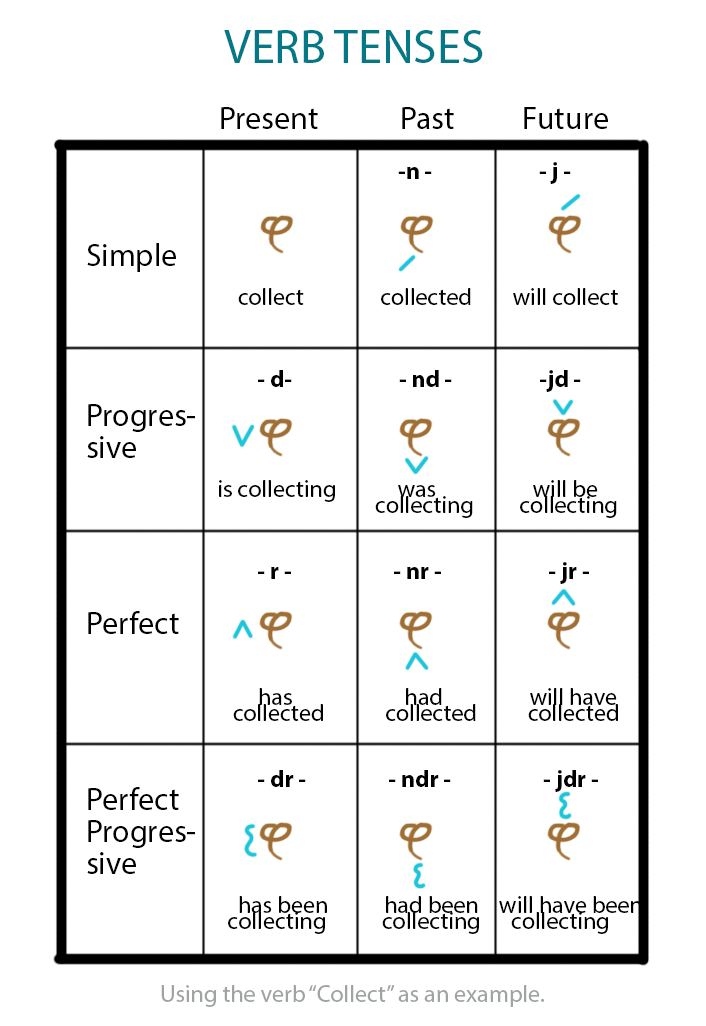

The chart above uses the verb ‘Collect’ as an example. The pronunciation of this word in Tapissary is ksemacr. (Note: please make sure to check the Speech tab for pronunciation. The k in Tapissary is pronounced like the J in July).

I collect …………..Yë ksemacr.

He collects ………….Hlë ksemacr.

The clerk collects……… Ze tenin ksemacr.

The clerks collect ………….Ze teniwn ksemacr.

Notice that the verb form is the same no matter the conjugation. This is true for the present tense as well as all the other tenses.

Above, we saw how the plural marker ‘W’ is placed after the accented vowel of a word. The same applies to verb tenses, with one extra twist. The verb tense snuggles right inside the accented vowel of the word. How is this done? The accented vowel in the verb ksemacr is a. We need to place the verb tense inside of the letter a. Let’s take the simple past tense, which is n, as an example. The a is doubled and accepts the n between them, like a sandwich. Ksemacr becomes ksemaacr in which we can now slip in the n (past tense), which gives: ksemanacr, which means collected.

All the rest of the verb tenses use the same formula:

I collected ……..Yë ksemanacr (the n is past tense)

She will collect ………Elë ksemajacr (the j is future tense)

The clerk will have collected ……….Ze tenin ksemajracr (the jr is the future perfect)

No clerks were collecting ………Ze tewnni ksemandacr (the nd is the past progressive)

In English, we have lots of suffixes and prefixes, but when a change rests right inside the root of the word, it’s called an infix. As you see above, the plural is an infix, and so are the verb tenses. Later we will see how the treatment of the prepositions is the same as the verb tenses… a kind of sandwich.

More to come as I work on text and images. The above new additions posted on Aug 7, 2022

BASIC GRAMMAR

All languages have grammar, but Tapissary has two layers of it, the basic shown here, and the cyclic is shown on another page. For an understanding of how the language functions, it is a good place to start here.

As I build this basic grammar page, explanations of various parts of speech will be described. One of the elements that may stick out is how concerned Tapissary is with space. This is natural, as I began creating it in 1977 while learning American Sign Language.

“An Interesting Word in a Book”

Questions in Tapissary do not reverse the verb and subject as they do in English. “But what is that word? What does it mean?” become ‘But that word be what? It mean what?’

There! Oh! Is it a fly? becomes ‘There! Oh! It be a fly?’

My thanks to the guys in German class who posed for the sketch above.

NOTE: as I construct this page, I’m posting some of the more advanced features first. If you are looking for the most basic things such as how to set up a simple sentence, my goal is equally to address that. In the meantime, here’s a teaser: you don’t have to worry about verb conjugation. I read, you read, he read, she read. I be, you be, she be, it be, etc… The only case present in Tapissary is the genitive (showing possession such as the teacher’S book, YOUR car, etc). No other cases exist, not even for the pronouns, such as in English, you say ‘I like HIM’. In Tapissary, you say‘I like HE’, and ‘please help ME’ becomes ‘please help I’. With this said, there is a semi-exception called the ‘Deputy Accusative’. It does not function along traditional lines of the accusative case. It is described lower down on this page.

Here are some more simple phrases:

To hear the 7 sentences above spoken in Tapissary, click the video.

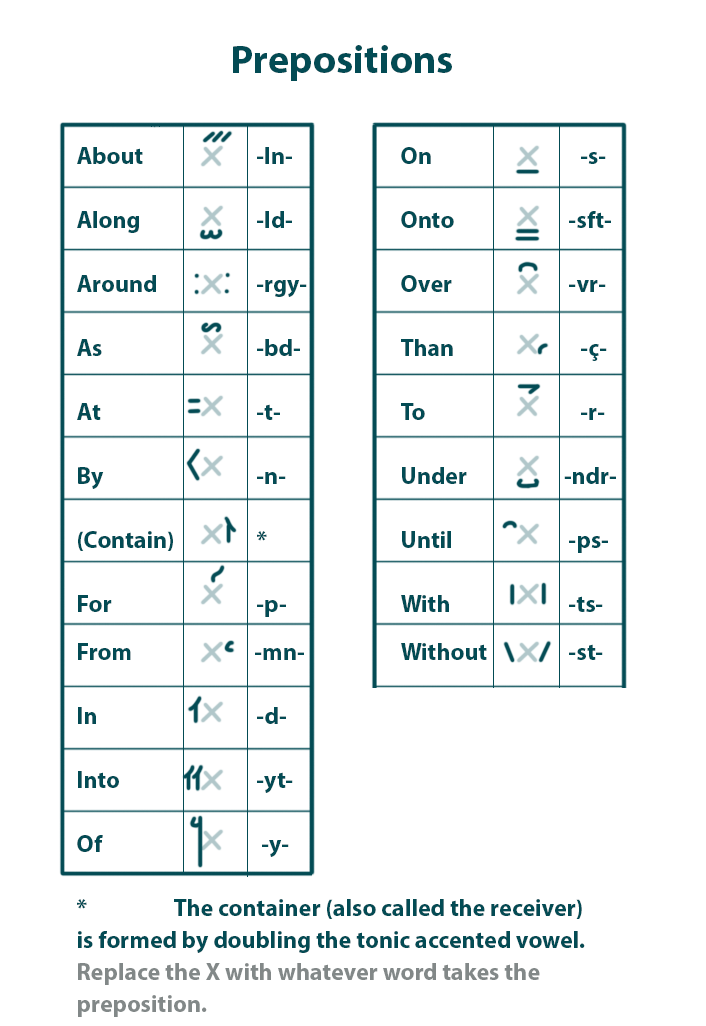

INFIXES

Before getting into the features of space, I will describe a device present in Tapissary that requires a little bit of dissection. Many languages use prefixes and suffixes, but here you will see that Tapissary often enjoys digging right into the core of the vocabulary words and creating infixes. I like to think of it as an anatomical approach. This is evident in prepositions, verb tenses, the negative, and the plural. To construct an infix, the accented syllable of the word becomes the starting point. As far as finding the accented syllable, Tapissary is very regular in its rules. The tonic accents fall at the end of each word, unless there is a doubled consonant. In such cases, the vowel before the double consonant is accented. I’ll use some English words as samples to make it easier for you to see what is actually going on. First, I highlight the accented syllable “perFORmance”, “HElicopter”, “RUby”. To make the plural, a W is placed after the accented vowel. This gives performances = perFOWRmance, helicopters = HEWlicopter, and rubies = RUWby.

Now for some examples in Tapissary:

Helicopter = xelicopptra Helicopters = xelicowpptra

Ruby = rubi Rubies = rubiw

The infixes for verb tenses and prepositions follow a similar pattern to the plural, but there will be an additional step. As mentioned above, the first step is to find the accented vowel. Let’s use the word xépballo, which means gift. The accent comes before the double consonant, so that the A is the accented vowel. The next step is to pull apart the word at that vowel, retaining the accented A on both the first part and second part of the divided word. The operation looks like this: xépba + allo. The preposition from the chart above can then be inserted between these two parts of the word, giving this result: xépba + pr + allo. The pr is the preposition meaning for. In other words, this is a gift FOR someone. Notice how the 3 parts of the word come into one finished word, retaining the accented syllable before the double consonant: xépbaprallo. Another example using ruby. That is rubi in Tapissary, and as there are no double consonants, the tonic accent comes on the last syllable, which is i. Splitting the word at the accented syllable, we get: rub + i, but remember that the accented i is attached to both ends of the split, giving rubi + i. The preposition will fit snuggly into the middle, and if we use FOR again, which is PR, the formula renders this word: rubi + pr + i. Rubipri, a ruby that is for someone or something. The accent falls on the last syllable. Here’s the finished formula: ACCENTED VOWEL + infix + SAME ACCENTED VOWEL. Let’s use it with the construction AT. In Tapissary, prepositions are always expressed in pairs. I am who is at someplace, and the school is that someplace that receives me. The infix for AT is ‘t’. The infix for CONTAINING/RECEIVING is ‘h’.

School = jcoulli I = yë I at = yëtë I am at the school = yëtë ir tö jcouhoulli.

Library = citabiñ I am at the library = yëtë ir tö citabiñhiñ.

The same with the verbs. The future tense is the infix ‘J’. Again, I’m using English words so it’s easier to see the internal changes of the word.

I will remember it = I remejember it. You will believe me = You beliejieve me.

The infix for the past progressive is the infix ‘ND’.

I was memorizing it = I mendemorize it. You were believing me = You beliendieve me.

And some examples in actual Tapissary:

remember = tonamos I will remember it = yë tonamojos il.

believe = bishvil You were believing me = siñ bishvindil yë.

Note: the formula: vowel + H + vowel, can be simplified to: vowel + vowel. Therefore, citabiñhiñ becomes citabiiñ. When this vowel + vowel structure comes at the end of a word, such as the example here, then the h sound which is not written, comes at the very end of that word and is pronounced. It would sound like: citabiiñh.

NEGATIVE

There are two ways to form the negative.

1) You can add sy or syë at the end of a verb. This older style (historically an added s at the end of a verb) is becoming outdated.

2) The more commonly used negative is formed by way of a‘broken infix’. The rest of this section addresses its formation.

A negative part of speech in Tapissary has its accented syllable broken. Since the negative negates whatever word it describes, be it a verb, noun, or adjective, you kind of break it apart then reassemble it into its new form. Take the accented vowel (or diphthong) of the word and exchange its place with the consonant or consonant cluster that follow it. If the word ends in a vowel as in the examples here, then the preceding consonant (or consonant cluster) is that which is switched.

Negated words ending with an accented vowel:

Have – xa

Not have – ax

Car - thota

No car - thoat

Book - cipbiñ

No book - ciiñpb

Notice - ilañ

Not notice - iañl

Happy - ënë

Unhappy - ëën

Unhappily - ëënla

Negated words ending with a consonant:

If two or more consonants come together and if they may be too hard to pronounce in their new positions, add the ë at the joint. For instance, pie is purtarj. If you want to say no pie, then you break the word apart like so, purt+arj > purt+rja > purtjra. While this might not present a problem of pronunciation for some people, it is a rather heavy consonantal cluster. By placing the ë between the two clusters seen in this example, it is easier to pronounce and hear. Purtrja would yield purtërja.

Other infixes do not conflict with the negative. On this word for pie, for instance, you can add the plural, and a preposition. The same rules described about other infixes apply without any modification to their position. It is entirely regular.

Examples:

A) on accented vowels on the last syllable.

Pie – purtarj

No pie – purtërja

No pies – purtërjaw

No pies at – purtërjataw

… … … … … …

B) On accented vowels that are not the last syllable.

Picture - pittour

No picture - pëttiour

No pictures - pëwttiour

No pictures in - pëydrëwttiour

.

Squeeze – caddig

Not squeeze – cëddaig

Did not squeeze - cënëddaig

Will not be squeezing - cëjdëddaig

VERB TENSES

Explanation in the making…

PREPOSITIONAL INFIXES

explanation texts in the making…

PAIRING UP

Prepositions come in pairs. There is the user of the preposition, and the receiver or container of that user. For instance, “I sit on the chair”. I am the one who is atop something, and the chair is what receives me from its position below me. “You go to the library”. You are the one who is headed toward someplace, and the library is the place that will receive your arrival. “The cat is in the cabinet”. The cat is who is inside something, while the cabinet contains her. One applies any of the prepositions in the chart above, onto the user of the sentence, and the receiver for all of them is CONTAIN seen on the graph. You may notice that there are only 16 prepositions above, and the 17th being CONTAIN. These are some of the most common, however, for the remaining prepositions, you use TO for instances when movement from one place to another is used, plus the other preposition which is not on the chart. “The cat went around the house”. Around is not in the chart above, but you will use TO in the phrase because a motion going from one place to another is indicated. This gives: “The to-cat went AROUND the contain-house”. How about “The cat sat around the house”. We are still using the word AROUND, however this time, it does not show movement from one place to another, the cat is just sitting there. So, you would say “The in-cat sat AROUND the contain-house”. While the preposition TO is used to show movement from one place to another in conjunction with those prepositions not on the chart, the preposition IN is used in conjunction with prepositions which do not move from one location to another.

APPLICATION OF THE PREPOSITIONS

For çelloglpyphs that are made of two easily separable components that do not touch each other, the prepositions in the above chart are inserted right into the center of that çelloglyph. For those that are not so cleanly divided into two pieces, the preposition is placed next to the çelloglyph in the manner illustrated in the chart, where the X represents the indivisible çelloglyph.

As for the pronunciation, whether the written çelloglyph is divisible or not, the accented syllable will be the place to insert one of the prepositions in the above chart. Remember that the tonic accent always comes on the last syllable of a word unless there is a double consonant, in which case, the accent precedes the double consonant. Cat = xatoul. The tonic accent falls on TOUL. To split the tonic accent, split it in two right at the vowel: XATOUL becomes XATOU + OUL. See how the accented vowel is doubled, so that it remains on the first half as well as the second half? Now, you can insert the preposition from above. Let’s use IN, which is ydr in Tapissary. XATOU + YDR + OUL = XATOUYDROUL. The word for car is thota. The accented vowel is the A. THOTA + contain + A gives, THOTAHA. this is the car which contains the cat who is inside of the vehicle. The H by the way can be dropped for simplicity. THOTAA. The H is still pronounced but at the very end of the word. The AA is also lengthened, so it sounds like AAH. Here is the finished phrase for ‘the cat is in the car’. Ze xatouydroul i tö thotaa. (the in-cat is the contain-car).

PASSIVE

The passive voice uses the prepositions BY and CONTAIN. Because the passive does not always show the instigator of the action, this is one of the cases where BY may not show up. “The cat was fed”. By whom? We do not know. This gives “The contain-cat fed”. There is no one mentioned as to who did the feeding. As in English, the agent remains a mystery and it is dropped. I refer to this dropping of the second half of a pair as an unfinished preposition. If you do mention the agent, then BY comes once more into play. “The cat was fed by my friend”. This gives : “The contain-cat fed my by-friend”. Another example: “She is being criticized by the press”. this gives: “Contain-she is criticizing the by-press”. The Deputy Accusative follows, where another instance of the dropped pair gives exception to the rule.

DEPUTY ACCUSATIVE

[Unpaired Prepositions]

There is no longer a traditional accusative case in Tapissary, however a particular usage of the ‘unfinished prepositions’ hooked onto the direct object makes it appear like one. While it does circuitously signal the direct object, its real function is to show that object in relation to a place which is yet unspecified. Using the deputy accusative is voluntary, it is not obligatory.

Here is how it works:

In a typical sentence with a direct object such as “I ate lunch”, there is no indication of placement included in the phrase. As Tapissary loves to show space, you have the option to add prepositions onto the direct object to show that a placement is suggested. The sentence would become something like “I ate lunch at”, or “I ate lunch in”, or “I ate lunch by”, etc… By adding a preposition, you allude to spatial placement, you just don’t complete the idea. The listener would simply imagine that you were somewhere for lunch, and if they wish, it’s a perfect opportunity to respond “and where did you eat lunch?” Here’s another example, “The professor will give an award”. Typically in Tapissary, you might say “The professor will give an award to”. End of sentence. The listener might ask, “To whom is the award going?” The unfinished prepositions may also be tagged onto the subject of the sentence if there are no objects. This is called the Deputy Nominative. “The cat is happy” may become “The in-cat is happy”. You don’t know where the cat is happy, but someplace is suggested.

In general, the deputy accusative is not used when a preposition is already applied to some part of the sentence. Example, “A man in the restaurant ate his lunch”. The word LUNCH is indeed the direct object, however, there is also a prepositional phrase ‘in the restaurant’, so there is no longer a need to suggest additional space. You can if you wish, but it is not considered very clean to say, “A man in the restaurant ate his lunch with”. In this case, just top off the sentence into a completed thought, for instance, “A man in the restaurant ate his lunch with his wife”. In other words, the deputy accusative is not a conspiracy against the direct object.

SPATIAL MAPPING WITH THE ARTICLE “THE”

Heading each of the six charts above are the six words for THE in Tapissary. The malleable form [ze] is used before flexible objects such as paper, rubber, skin and therefore animal and human life, as well as plants. The liquid form [la] is used with any kind of liquids from water to molten silver. The form of gasses [ré] include air, fire, as well as time such as days, hours, seasons, etc. The solids form [ji] takes in rather hard surfaces such as wood, stone, metals. The abstract form [sö] is used for things without a physical form, such as a thought, the heat, desire, etc. The composite form [tö], listed above as the combinations form, describes when two or more of the categories listed above apply. For instance, if you say you are going to stay at the hotel, that building is certainly a solid, but the comforts inside are malleable, as well as the people there. You have the freedom to interpret the categories. For instance, you could use the solids form of THE to say: The (solids) air pollution made me tired. This is like saying the air was so thick it was like a rock. Take the case of the computer. When you purchase the device, it is a box, solid and hard so that the computer = ji conon. However, when you are using a computer, the airspace around you melds into the virtual space where your brain may feel that space on the flat computer screen has depth. Therefore, you would say ré conon for the computer. The same goes for a book which has malleable pages rendering the book as ze cipbiñ. However, when you read a text, your mind is carried into the airspace of the story or article, and the book becomes ré cipbiñ. There is some degree of flexibility in choosing which form of THE you need.

In addition to the article THE describing the physicality of the noun, it can also show spacial placement.

THE is the only article which describes space. There are 186 words for THE, however you will see on the graphs that they are regular once you understand the pattern. All the other articles can pair with the article THE if you wish to establish placement. If you say, I see a rabbit, and wish to state that the rabbit is right in front of you but at a mid distance, you will need the article ZET which is one of the 186 forms of the word THE. The article A has only one form, so if you wish to say A RABBIT, but indicate it is in front of you at a medium distance, you place ZET before A RABBIT. So it would be like ‘I see the a rabbit’ where the form of THE is zet. In Tapissary, this gives ‘Yë den zet biñ lapiñ’.

To Note: The blue-green X’s on the graphs represent the words that may follow the article.

Example:

The rabbit (facing, or in front of the speaker, at a mid distance) the article ZET is written flush with the rest of the celloglyphs on that line of script. See how the X’s are in line with the character for ZET. However, let’s say the rabbit is below the speaker at a close distance, the article ZAZAC would be used, and notice how the article and the word for rabbit would physically be lowered from the rest of the sentence. In the sample on the chart, the first X after zazac represents the rabbit, and the two other X’s above right represent the placement of the rest of the sentence. The spacial distance is somewhat reflected in the physical script. If it is lower, then lower the article and object as described in the charts above.

Here is an example of layering where the article written in its BELOW form is literally shown below the rest of the sentence. It is repeated twice in this text, it looks like a capital E knocked over onto its back and having grown a long tail. It is the article THE in its solid form. The charts above are in the forward form, but the following text is in the backward form. If you go to the tab BACKWARD SCRIPT, you will find the backward forms of the article THE. They are used in the same way as the forward forms shown above.

Translation: “Prophetic question: Why did the chicken cross the road? Answer: To get to the other side”.

Note: using the spatial forms of THE can convey other types of subtleties in addition to indicating where on the grid the object is located. Take for instance wearing something on your body. Usually, by default, you could choose these two coordinates from the graph: FACING and TOUCHING (as it is touching your body). “You are wearing the a shirt” becomes “Siñ tradaggë zeç biñ bëthiz”.

However, say you are wearing a coat because it is cold outside. The purpose of the coat is to keep you warm. I don’t know if everyone is the same here, but for many, when they take a dip in the cold ocean, their backs are more sensitive than their fronts, legs, arms or head. Therefore, with wearing a coat in the context of a cold day, one might choose from the graph BEHIND and TOUCHING. Behind means the back part of the body, because this is where the coat is most appreciated. “I wear the coat” becomes “Yë traggë zaç mañto”. The same can be said for jewelry. “I wear the bracelet” where that is on the SIDE (of the body) and TOUCHING (the wrist). “Yë traggë zenoç vxaxiolli”.